The Wang 1200 was an unsuccessful product, at least in terms of Wang's original expectations, but it played an important role in the history of Wang Labs. It is also interesting in the more general context of the development of word processing as a standard part of office automation.

Please visit the History of Wang Word Processing page for some context about how Wang came to develop the Wang 1200 and how it related to Wang's other word processing products.

Wang 1200 Introduction (link)

The Wang 700 programmable calculator had been very profitable for Wang Labs, but profit margins were declining as competition increased in the produce space. Dr. Wang was astute enough to foresee that electronic calculators would eventually be reduced to a single chip, and needed a way out of the calculator market.

Part of his strategy was to move into the general purpose computer market. The other half of this strategy was to create a word processor as part of a larger desire to penetrate more deeply into mainstream corporate markets.

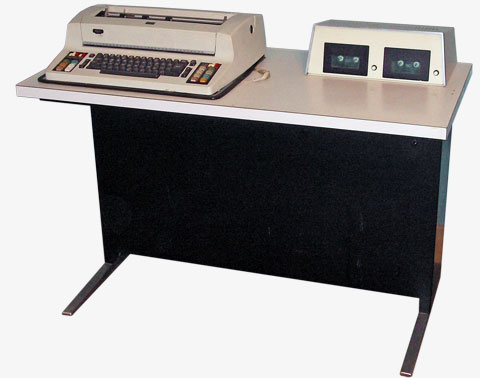

Wang realized that they could take the 700 calculator, which already had the interfaces to the IBM Selectric typewriter and digital cassette drives for data storage, and rewrite the microcode program and turn the calculator into a word processor.

After about a year of development, the 1200 was announced in November, 1971, a few months before it was ready to ship to customers. The 1200 had a rocky start in terms of reliability, and Wang struggled to gain much of a foothold against IBM, which was entrenched in this market space with their MT/ST product.

Wang soldiered on, developing a few derivative products and making some refinements, but nothing helped. Despite the lack of success, it gave Wang some needed experience such that their next attempt at a word processor, the Wang WPS, was a huge hit.

1200 Capabilities (link)

This section is a quick overview of the machine's operation. Please go to the documents page and read an official manual if you care to understand how the machine was really operated.

The Wang 1200 was built at a time when RAM was very expensive, as semiconductor RAMs were just beginning to edge out core memory as the cheapest solution. As a result, the 1200 had only 256 bytes of RAM. 100 bytes were used as an I/O buffer to the cassette tapes; 100 more were used to hold the line currently being edited or printed; the rest, presumably, were used by the microcode to hold working variables. This limitation greatly affected the style of editing.

The 1200 had four main modes of operation:

- RECORD

- PLAY

- TRANSFER

- EDIT

These modes were combined in different ways to perform typical editing tasks.

Simple Document Creation

In RECORD mode, the typist entered text as normal. Mistakes could be corrected by hitting backspace, overstriking a character, forward spacing over any still-correct text, etc. All of this was presented on the paper as if it was a normal Selectric. When the RETURN key was hit, in addition to the usual Selectric behavior, the 100 byte line buffer was saved to cassette. Each line was stored on tape as a fixed sized 100 byte block.

If the typist realized they had made a mistake on a previous line, they could hit BACK-LINE to rewind one block on the tape. The line had to be retyped entirely and then recorded over when RETURN was hit again. Normally this shouldn't have been used too often.

At the end of the document, the typist would rewind the tape, load a clean sheet of paper into the Selectric, and start PLAY mode. In PLAY mode, the 1200 would reach each block of data from the tape and print it, resulting in the final copy containing all previous corrections which had been made during the document entry.

During PLAY mode, the operator had the option of stopping at any point, then advancing by character, word, or line. The operator could then request characters, words, or lines to be skipped, and could manually enter text to the paper without committing it back to the tape. This was useful for one-off corrections instead of having to make a full edit on the document.

While playing back a document, the operator could specify either that each line was printed as-is ("SAME" mode), or that it should be formatted ("ADJUST" button). Adjust means that all the lines of a given paragraph would be run together and then broken into lines based on the margins. The result could simply be broken or the lines could be justified to produce an even right edge.

Control Codes

While entering text, the operator could also insert non-printing control codes. These codes affected the formatting of the document when it was ultimately printed, including things like:

- set tab stops

- set page margin

- set page length

- set the adjust zone (band where word breaks occur)

- set line spacing

- specify behavior at the end of each page

- center, align, justify text

- specify formatting of numeric data

- specify field codes for form letters

- mark end of page

- mark end of document

In Place Editing

By pressing RECORD and PLAY at the same time, the edit mode was invoked. This was very similar to the simple editing during playback option described in the previous section. However, as each line was modified, it was also saved back to tape. Because of the fixed format of the tape file, there was no way to insert lines of text, although lines could be deleted. As each line was printed, any edits made by the typist were recorded over the 100 byte block representing that line on the tape.

To create a change in the middle of a page, it was often faster to use the SEARCH feature, where a simple literal text match was used to locate a specific line in the document.

Transfer Editing

This mode was entered by selecting the TRANSFER button. TRANSFER mode took advantage of having two tape drives. Each line of text was read from the first cassette tape into the memory buffer. The operator could keep the line, edit it, or even add new lines. All lines which were kept or were newly created were sent to the second cassette tape drive. This mode allowed more general editing operation that was not possible with the single cassette tape.

Document Merge

This mode also took advantage of the two cassette drives. One drive held a form letter or other template. Fields within the document were marked with special control codes. During playback, whenever such a code was seen, data was read from a simple linear "database" on the second tape drive. For example it might have contained a series of records containing the customer name, address, and phone number.

A related mode of operation was to play back the form letter, but each time one of the data fields appeared, the printer would stop and wait for the operator to manually enter each field.

Tape Format

As was mentioned earlier, each line of text was store on tape as a fixed block of 100 bytes. There was a switch to select recording each line either once or twice. The double record mode slowed things down a bit and reduced the effective capacity of the tape, but it meant that there was far smaller risk of losing a line of text due to a dropout on the tape.

The Wang 2200, introduced a couple years later, always recorded in double block mode, but by default it used 256 byte blocks. In order to allow transferring files between the 2200 and the 1200, though, Wang BASIC had syntax to allow specifying a block size of 100 bytes.